Key points

- The recent housing construction boom alleviated some supply shortages, increased national vacancy rates and decreased rental growth.

- But, residential construction has been declining since late 2018, dragging on GDP growth, retail and employment. Residential construction should bottom in mid-2020.

- Supply issues could become a problem again because building approvals are running below underlying housing demand (which remains high from population growth). Local and state governments have a role to play in land release planning.

- We expect national home prices to continue rising over the next few months and exceeding their peak with home prices rising by around 10% in 2020 and 5% in 2021.

Introduction

The downturn in Australian home prices from September 2017 to June 2019 and the associated hit to household wealth and spending was a major drag on the Australian economy. In this Econosights we update our views on the Australian housing market. Our forecasts for the key areas of housing are below:

Source: ABS, AMP Capital

Housing demand and the supply shortage

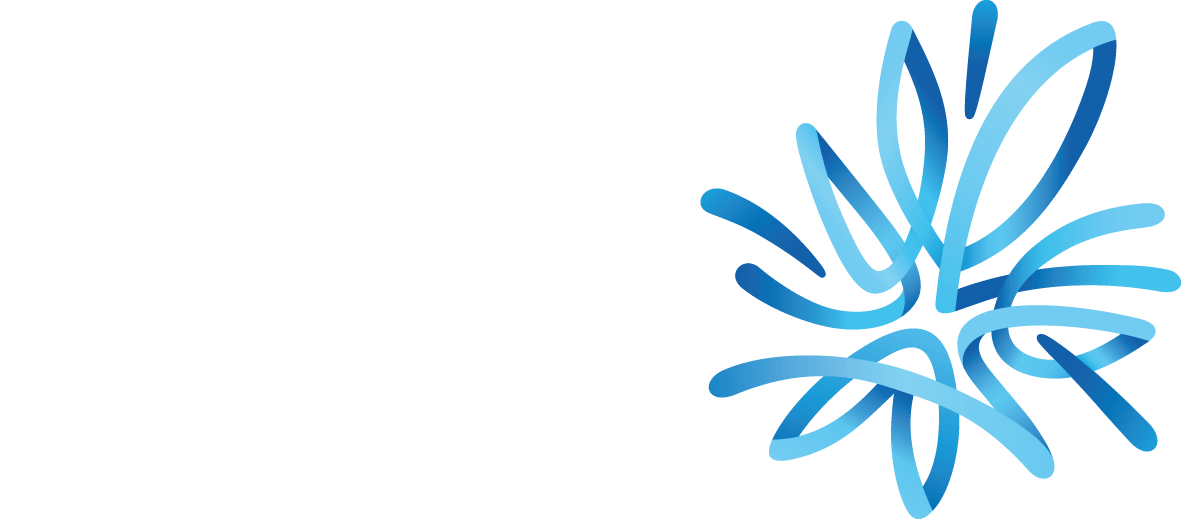

Underlying housing demand is determined by population growth (adjusting for the number of people per dwelling). Housing supply is measured by the number of total homes built or “completions” and we allow for knockdowns, conversions and vacant properties=news. In Australia, housing supply was running well below demand in the mid 2000’s as population growth took off (see the above chart) which created some shortage of new dwellings.

Source: ABS, AMP Capital

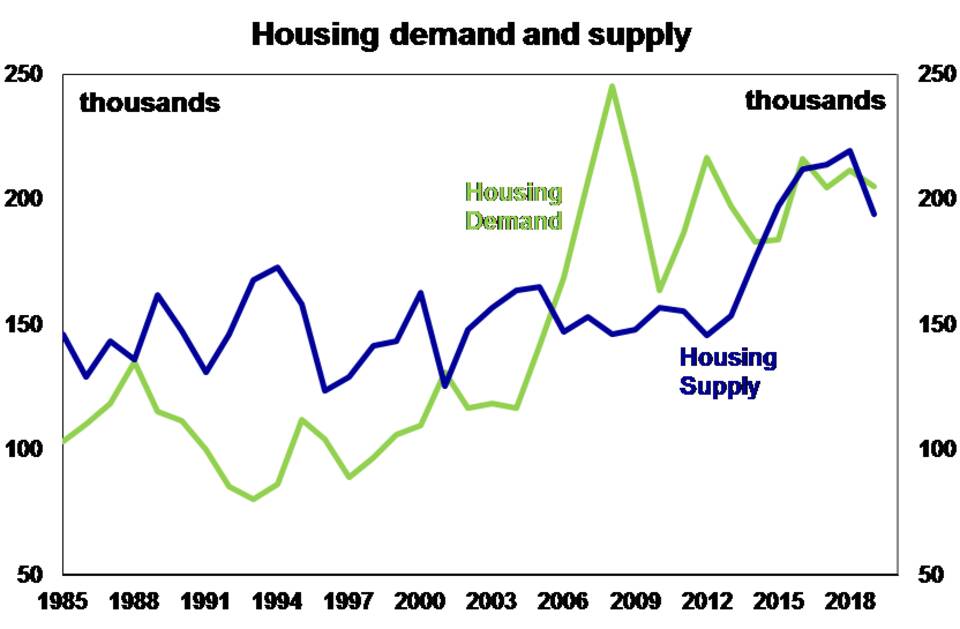

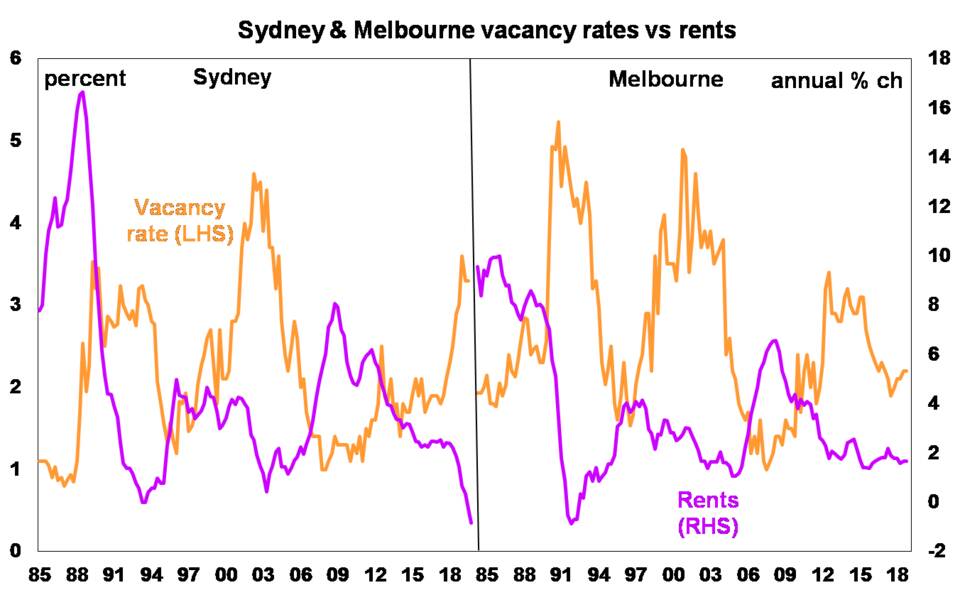

This housing supply shortage decreased national vacancy rates, caused a spike up in rental growth over 2006-09 (see chart below) and contributed to the fast increase in home prices over the past two decades.

Source: ABS, AMP Capital

The last home price boom (from 2012 to mid-2017) lifted dwelling prices by nearly 150% (from trough to peak). The price boom also spurred on a big rise in housing supply which partly offset previous years of underbuilding, bringing housing demand and supply closer into balance.

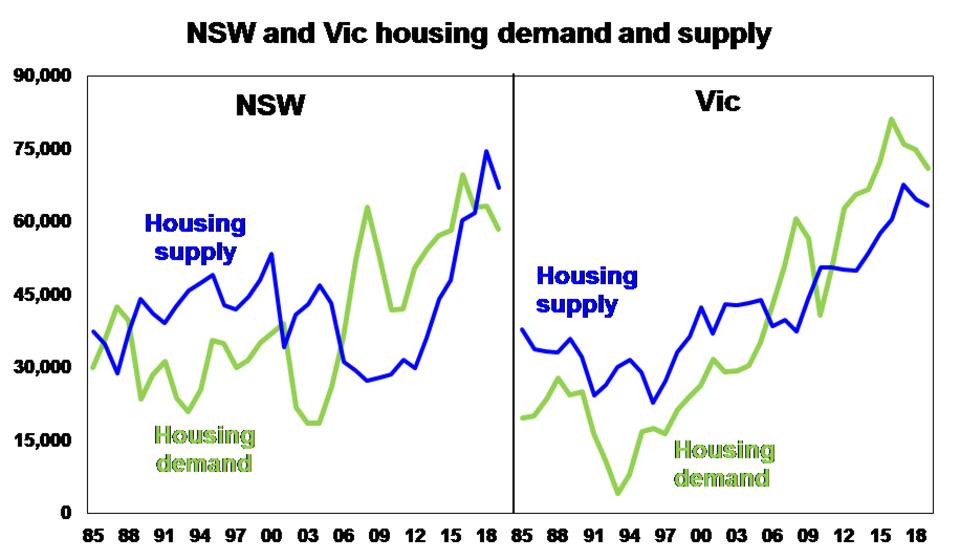

The housing construction boom that started in 2012 was concentrated in New South Wales (NSW) and Victoria (Vic), which makes sense as these two cities account for 40% of the population. The lift in new housing construction over the past few years, has closed the supply shortage in NSW (for now) but there remains a supply shortage in Vic. Vic housing demand is high because of strong population growth in the state (2.1% per annum versus 1.5% in Australia and 1.4% in NSW) – see the chart below.

Source: ABS, AMP Capital

This housing stock shortage in Vic is evident in higher rental growth and lower vacancy rates in Melbourne compared to Sydney. Annual rental growth in Sydney is now running at its lowest pace in history (see charts below).

Source: ABS, AMP Capital

The outlook for housing construction

The recent housing construction cycle peaked in 2018. Building approvals (the best leading indicator for housing construction activity) are now 60% below their 2018 peak levels. At its high, new housing construction accounted for 6% of GDP and we expect it to bottom at 5% of GDP in mid-2020, which means a total 1 percentage point detraction from GDP growth.

Building approvals need to be running around 18K/month to keep up with demand (which remains high because of migration). However, approvals are only tracking at around 15K/month. The risk is that housing demand will start to track above new supply again which will push vacancy rates down and put upward pressure on home prices and rents (again).

The government (state and local) has a role to play in housing planning, especially through land release. The global experience suggests that rules-based housing planning systems (like in Germany) deliver higher housing construction compared to discretion-based systems (like in Australia) which can often be delayed or blocked by local residents.

Housing lending and credit

Housing lending growth is currently up by 21% from its bottom in mid-2019 with a larger rise for owner-occupiers than for investors. There is further upside for housing lending as lower interest rates have unlocked more housing demand. But housing credit growth is likely to remain well contained between 3-4% per annum as households are still focussing on paying down debt. For now, there doesn’t appear to be any risk of macroprudential policy being required to stem financial stability risks, but it may become so if credit growth picks up.

First home buyers are coming back as a share of the market, currently making up 20% of total new loans (close to a record high) and the governments First Home Loan Deposit Scheme is helping (although it is only available to 10,000 applicants so far which is only around 10% of annual first-home buyers) and is probably just adding to home price growth.

Outlook for home prices

The current upswing in home prices that started in June-2019 has room to go further. Sydney home prices are around 5.4% below their highs and Melbourne prices are 1.2% below the high and these will be surpassed over the next few months, especially as we expect two more RBA interest rate cuts over the next 6 months which will fuel additional demand for housing, as the cost of borrowing falls. However, after mid-year we expect the pace of growth in home prices to slow. There are a number of factors which will limit home price growth (especially when compared to past housing recovery cycles) which include: higher household debt to income ratios (which are at a record high), tighter bank lending standards, more unit supply to enter into Sydney and Melbourne property markets and a weak economic backdrop. We expect national home prices to increase by around 10% in 2020. After 2020 we expect price growth to be more moderate, around 5% per annum. The lift in home prices is also extending regionally with moderate gains in Brisbane, Hobart and Canberra. Perth prices are finally stabilising after years of declines while Darwin prices are still declining.

The downturn in housing subtracted around 1-1.5 percentage points from consumer spending. Rising home prices will provide some offset but household spending should still remain constrained due to low wages growth weighing on spending. And now there is also the risk to consumption from bushfires and lower tourist spending from the Coronavirus.

Implications for investors

Residential investment has performed well in Australia over the long-term, providing similar returns to sharemarkets (at 11% per annum) while also providing diversification from listed markets. In Australia, housing as an investment is especially favoured because of historical fixation around owning your own home and the taxation benefits (negative gearing, capital gains tax discount and favourable concessions in self-managed superannuation funds). Despite our expectations for moderate capital and rental growth in housing nationally over the next few years, the favourable tax treatment of housing in Australia still makes it an attractive investment, especially while bond yields are so low.

A broader issue around exceptional home price growth is around the impact on inequality. Tensions around inequality and housing affordability have been evident across manty developed nations including the Hong Kong protests, arguments for Brexit and support for far-left Democratic candidates (like Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders) in the US. While low interest rates have improved housing serviceability in Australia over recent years, affordability concerns are still an underlying issue, especially in Sydney and Melbourne and could become an issue when interest rates eventually start rising again.