The Australian economy slowed in 2019 to its slowest pace in ten years as private spending growth collapsed.

The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) sees the economy being at a “gentle turning point” before a reacceleration in 2020. We are sceptical of the RBA’s optimistic forecasts and see Australian GDP growth remaining constrained around 2% over 2020/21 (see the forecasts table below), well below Australia’s potential growth of around 2¾% which means that spare capacity will remain a problem, keeping inflation and wages growth low. We outline our views for Australia in 2020 in this Econosights.

Economic forecasts

Consumers

Consumer spending is a vital component to the growth outlook, accounting for 60% of GDP. Household spending is growing at just over 1% annually, its lowest rate of growth since early 2009, and growth will remain low in 2020/21.

The household savings ratio has fallen from 8% in 2015 to 4% (on average) in 2019 as households dipped into savings to finance spending (but the savings ratio has been rising recently thanks to government tax cuts). We expect the savings ratio to remain elevated around 5% over the next few years. Household debt has also increased from 170% of income in 2015 to 191% currently, with increases mainly in housing debt. With household debt already being elevated and much higher compared to global peers, further increases in household debt will be smaller while wages growth is low. Although, serviceability of debt isn’t a major problem for now as interest rates are so low.

Higher home prices generally lift consumer spending through the “wealth effect”. The boom in home prices over the past six months will provide some boost to households over 2020 but it may not stimulate spending as much this time round given the backdrop of poor consumer sentiment, low wages growth, high household debt and a rising unemployment rate.

Lower interest rates and tax cuts have not worked as well as expected in lifting spending. Further rate cuts will support those with a mortgage, but the benefits diminish as mortgage rates are unlikely to fall much more. Further tax cuts would be beneficial to give back some of the recent income tax bracket creep.

Employment, wages and inflation

Labour underutilisation (sum of unemployment and underemployment) in Australia is very high at 13.8% of the labour market (much higher than the 7% in the US and only slightly better than the 15.7% rate in the Eurozone) which is limiting wages growth. To get underutilisation down, labour demand needs to increase via higher employment growth and hours worked. However, the leading indicators on employment growth (including job advertisements, hiring intensions and job vacancies) are indicating lower employment growth ahead and we expect employment growth to slow to below 2% annually and the unemployment rate to trend higher to 5.5%.

High labour underutilisation and low productivity growth mean that wages growth is likely to remain at just over 2% annually for the next two years which will also keep inflation low. Price discounting in the retail sector will also drag on inflation and underlying inflation is expected to increase slowly towards 2% over the next three years, missing the RBA’s 2-3% target band. Price growth for essential services like health, education and transport (that are often provided by the public sector) will continue to run above the rate of inflation.

The housing market

The current divergence in the housing market is the phenomenal boom in home price growth (tracking at an annualised pace of around 20% over the past few months) against falling housing construction. Interest rate cuts, an easing in lending standards and the removal of risks around negative gearing and the capital gains tax discount have been driving home prices higher, particularly in Sydney and Melbourne. Pent-up housing demand and low home listing are super-charging prices. We expect solid dwelling price growth in 2020, lifting by around 10% nationally.

Price gains will be strongest in Sydney and Melbourne but are also broadening out to other capital cities. Prices in Perth look to be starting to recover after years of price falls. After the strong run-up in prices over 2019/20 we expect more moderate home price growth of around 5% over the next few years from the impacts of higher household debt, tighter bank lending standards and a weaker economic backdrop.

Residential construction will continue slowing following the run‑up in construction from 2014-17 but should reach a bottom in mid-late 2020 before flattish growth over 2021.

The investment outlook

Business investment declined in 2019 but the outlook for business investment is mixed. Mining investment is rising again after declining for the past six years. However, mining is now only 2% of GDP whereas at its peak it was 7% of GDP so rising mining investment will not add as much to growth as it did at its peak. Non-mining business investment has been tracking at around 4.5% of GDP for the past 8 years and the forward-looking capex survey indicates that non-mining business investment is likely to be flat or fall slightly over 2019-20.

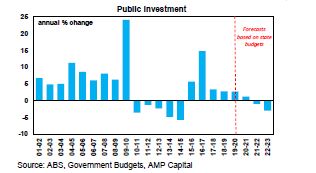

Public investment growth is strong with the government undertaking significant transport infrastructure spending over the past five years. Government budgets indicate that public investment growth will be contributing to GDP until a peak around 2021-22 (see chart below). Although, given the interest in infrastructure spending this peak could be pushed out again.

The reliance on exports

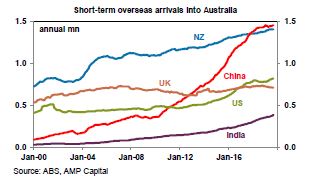

Australia’s major exports are commodities, education services, tourism and agricultural exports with around one-third of exports going to China. China’s investment-intensive boom and growth in the middle-income population over the past decade has been a significant driver of demand for Australian goods and services. Chinese tourists now make up the most inbound short-term arrivals (see chart below) but the growth in Chinese arrivals for education and tourism have slowed over the past year.

Chinese GDP growth is slowing, to around 6% per annum, but at this rate of growth there will still be solid demand for Australian exports and export growth will make a positive contribution to GDP over the next few years.

More stimulus is necessary

Constrained GDP growth, no signs of a pick-up in inflation and a rising unemployment rate means that we expect more RBA interest rate cuts in February and March with the cash rate ending 2020 at 0.25%. The RBA is also likely to start quantitative easing once the cash rate reaches 0.25% which will initially take the form of government bond purchases.

Tax cuts would be more ideal for lifting consumer spending. The government could bring forward the next tranche of legislated tax cuts (due to start from 2022) which would involve increasing the 32.5% bracket from $90K to $120K (which is worth around 0.6% of GDP annually). Although there is room in the budget for some of this tax stimulus, the government’s commitment to bringing the budget back to surplus in 2019/20 is taking priority and tax cuts may not happen until the budget is released in May 2020.

The Federal government recently announced some extra fiscal stimulus, but it is small and only worth 0.1-0.2% of GDP which includes drought assistance, extra funding for aged care and bringing forward some infrastructure spending.

Risks to the outlook

The risks to the growth outlook are mainly to the downside. Globally, the things of most concern are: a weakening global growth environment (that could come from a US recession, a renewed deterioration in the US/China trade situation and a sharp slowing in Chinese growth). This would hit demand for Australia’s exports and the domestic sharemarket. However, in this environment the $A would probably depreciate which would provide some support for Australia. Changes in the $A are a big source of risk for growth. The RBA estimates that a 5% appreciation (depreciation) of the $A decreases (increases) GDP growth by 0.5%. We expect the $A to remain range-bound between $US0.65-0.70 over 2020 with upside pressure on the currency coming from a high terms-of-trade and a weakening $US but downside pressure from the RBA cutting interest rates.

The other major risk is that housing construction could decline further with jobs growth falling by more than expected which could mean a higher unemployment rate.

Upside risks to growth include stronger home price growth (which could result in a restart of macroprudential policy) which would increase consumer wealth and spending.

Implications for investors

While the Australian economy weakened over 2019, attractive valuations against falling bond yields, okay earnings growth and expectations of interest rate cuts lifted sharemarkets to a record high. Despite our subdued outlook on the Australian economy in 2020, these same factors are still in place to varying agrees and along with an improving global growth environment are expected to lift Australian shares over the next year. Although, performance is unlikely to be as strong in 2020 as in 2019.